Energy for the Future

Harnessing the energy of the sun and stars to meet the Earth's energy needs has been a decades-long scientific and engineering challenge. While a self-sustaining fusion burn has been achieved for The thermonuclear fusing of hydrogen atoms from water in fusion power plants may someday supply virtually unlimited electricity.brief periods under experimental conditions, the amount of energy that went into creating it was greater than the amount of energy it generated. There was no energy gain, which is essential if fusion energy is ever to supply a continuous stream of electricity. If it is successful, the National Ignition Facility will be the first inertial confinement fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and a self-sustaining fusion burn. In the process, NIF's fusion targets will release 10 to 100 times more energy than the amount of laser energy required to initiate the fusion reaction.

The thermonuclear fusing of hydrogen atoms from water in fusion power plants may someday supply virtually unlimited electricity.brief periods under experimental conditions, the amount of energy that went into creating it was greater than the amount of energy it generated. There was no energy gain, which is essential if fusion energy is ever to supply a continuous stream of electricity. If it is successful, the National Ignition Facility will be the first inertial confinement fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and a self-sustaining fusion burn. In the process, NIF's fusion targets will release 10 to 100 times more energy than the amount of laser energy required to initiate the fusion reaction.target capsule,  a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

A fusion power plant would produce no greenhouse gas emissions, operate continuously to meet demand, and produce shorter-lived and less haza The nuclear power plants in use around the world today utilize fission, or the splitting of heavy atoms such as uranium, to release energy for electricity. A fusion power plant, on the other hand, will generate energy by fusing atoms of deuterium and tritium—two isotopes of hydrogen, the lightest element. Deuterium will be extracted from abundant seawater, and tritium will be produced by the transmutation of lithium, a common element in soil. When the hydrogen nuclei fuse under the intense temperatures and pressures in the NIF rdous radioactive byproducts than current fission power plants. A fusion power plant would also present no danger of a meltdown. a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.Because nuclear fusion offers the potential for virtually unlimited safe and environmentally benign energy, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has made fusion a key element in the nation's long-term energy plans.

The goal of the National Ignition Facility is to achieve fusion by compressing and heating a pea-sized capsule containing a mixture of deuterium and tritium with the energy of 192 powerful laser beams. This process will cause the fusion fuel to ignite and burn, producing more energy than the energy in the laser pulse and creating a miniature star here on Earth (see How to Make a Star). With NIF, conditions are ideal for achieving fusion ignition, fusion burn and energy gain.

Ignition experiments at NIF will set the stage for one of the most exciting applications of inertial confinement fusion one could imagine—production of electricity in a fusion power plant.

To learn more about NIF's efforts to lay the groundwork for fusion energy—clean, safe, abundant energy for the future—visit the Laser Inertial Fusion Energy (LIFE) page on this Website or visit the LIFE Website.

Understanding the Universe

An artist's impression of Supernova SN 2006gy, the brightest supernova recorded to date.

An artist's impression of Supernova SN 2006gy, the brightest supernova recorded to date. Some of humankind's greatest intellectual challenges have to do with understanding how the universe began, how it works, and how it will end. A study by the National Research Council, Connecting Quarks to the Cosmos, produced a list of eleven questions that are crucial to advancing this understanding. Research at the National Ignition Facility could help answer five of these questions:

What is the nature of dark energy?

Scientists now believe that more than two-thirds of the universe consists of dark energy, a mysterious force that may be causing the universe to expand at an ever-faster rate. Attempts to deal with this question are in their infancy, but are currently more directed toward how dark energy acts than what it is. As a result, it will continue to be studied through one of the means by which it was discovered: using "Type Ia" supernovae—exploding stars—as the "standard candles" or measuring sticks with which cosmological distances are determined.But confidence in these measurements requires a detailed understanding of how these supernovae explode. Remarkably, computer simulations have shown that they are subject to the same hydrodynamic instabilities that affect inertial confinement fusion, the process at the heart of much of NIF's research (see How to Make a Star). NIF, then, will provide a unique way to study and understand these instabilities in the laboratory.

These same hydrodynamic instabilities also affect core-collapse supernovae, a different class of exploding stars that is also of great interest to astrophysicists. Understanding the explosion mechanism of these "Type II" supernovae has been a persistent problem in astrophysics for several decades. Current efforts appear to be focusing on instabilities as at least a factor in these huge explosions.

“The next two decades could see a significant transformation of our understanding of the origin and fate of the universe, of the laws that govern it, and even of our place within it.”

—Committee on the Physics of the Universe,

National Research Council

Did Einstein have the last word on gravity?

According to Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, gravity results when any object with mass, such as our sun, warps the space and time around it. Determining if Einstein was right necessitates studying the objects in the universe that provide the most extreme gravitational effects—the supermassive objects in the center of galaxies called black holes, whose gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. Of course, black holes cannot be studied in the way that astronomers study most objects, by observing the light that they emit. The matter that swirls into a black hole, however, will be subject to an extraordinarily hostile environment. This means that this matter will be in a highly ionized state—the atoms will have been stripped of nearly all of their electrons. The radiation that results will be characteristic of those ions, so understanding them will provide a vast amount of information. Such ions are difficult to study in the laboratory, however, because the conditions that produce them are so extreme. NIF will be able to produce such ions in its intense x-ray environment and will provide data that will directly affect our ability to understand what is going on in the matter that surrounds a black hole.Ions in very high ionization states also affect other astrophysical environments, so the studies that will further our understanding of black holes will also provide insights into other astrophysical sites, such as the accreting neutron stars that produce x-ray bursts, and the regions around active galactic nuclei. The detailed knowledge of highly ionized ions will provide essential information about temperatures and densities in such extreme environments.

How do cosmic accelerators work and what are they accelerating?

The highest-energy cosmic rays in the universe have energies of around 1020 (100 quintillion) electron volts, many orders of magnitude greater than the highest energies that can be achieved in modern particle accelerators. How cosmic rays achieve those energies is not known, however; this is one of the questions posed by the NRC. NIF will produce extraordinary electric and magnetic fields in its most energetic shots, and thus should provide an environment in which particles acting in such extreme fields can be studied.What are the new states of matter at exceedingly high density and temperature?

NIF will provide the highest temperatures and densities that have ever been created in a laboratory environment, enabling experiments to produce states of matter unlike any previously achieved. These studies clearly will improve our understanding of materials in extreme conditions, and may also further our knowledge of stellar evolution, as well as of the inner structure of the largest planets such as Jupiter and Saturn.How were the elements from iron to uranium made?

The stellar processes that synthesize, or create, the different isotopes of the heavy elements have been studied for several decades, yet science has not identified the exact location where the process that creates half of the heaviest elements, known as the r-process (for "rapid"), occurs. The properties of this process are well established by the nuclear physics of the nuclei synthesized in it—but whether it occurs in core collapse supernovae, in colliding neutron stars, or in some other site is not yet known. NIF will be able to shed light on this question in several ways. It may provide an environment in which some of the reactions that affect the r-process can be studied—primarily because of the high energy density that NIF will achieve. It also may, because of its very high neutron density (as high as 1033 neutrons per cubic centimeter per second), even be able to create some of the neutron-rich nuclides that will help scientists better understand the properties of those nuclei as they are synthesized during the r-process.NIF will enable other studies in nuclear astrophysics besides those associated with the r-process. NIF's extreme conditions will make it possible to study nuclear reactions at energies that would be difficult to achieve in experiments with a beam from a particle accelerator and a conventional target. This is primarily a result of NIF's extremely high density, but it also depends on some other special features of the NIF environment.

Inertial Confinement Fusion:

How to Make a Star

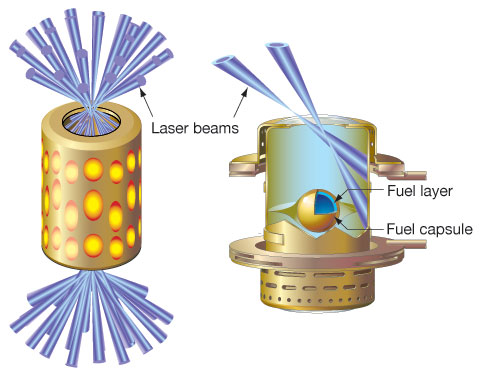

All of the energy of NIF's 192 beams is directed inside a gold cylinder called a hohlraum, which is about the size of a dime. A tiny capsule inside the hohlraum contains atoms of deuterium (hydrogen with one neutron) and tritium (hydrogen with two neutrons) that fuel the ignition process.

All of the energy of NIF's 192 beams is directed inside a gold cylinder called a hohlraum, which is about the size of a dime. A tiny capsule inside the hohlraum contains atoms of deuterium (hydrogen with one neutron) and tritium (hydrogen with two neutrons) that fuel the ignition process. The idea for the National Ignition Facility (NIF) grew out of the decades-long effort to generate fusion burn and gain in the laboratory. Current nuclear power plants, which use fission, or the splitting of atoms to produce energy, have been pumping out electric power for more than 50 years. But achieving nuclear fusion burn and gain has not yet been demonstrated to be viable for electricity production. For fusion burn and gain to occur, a special fuel consisting of the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium must first "ignite." A primary goal for NIF is to achieve fusion ignition, in which more energy is generated from the reaction than went into creating it.

NIF was designed to produce extraordinarily high temperatures and pressures—tens of millions of degrees and pressures many billion times greater than Earth's atmosphere. These conditions currently exist only in the cores of stars and planets and in nuclear weapons. In a star, strong gravitational pressure sustains the fusion of hydrogen atoms. The light and warmth that we enjoy from the sun, a star 93 million miles away, are reminders of how well the fusion process works and the immense energy it creates.

Replicating the extreme conditions that foster the fusion process has been one of the most demanding scientific challenges of the last half-century. Physicists have pursued a variety of approaches to achieve nuclear fusion in the laboratory and to harness this potential source of unlimited energy for future power plants.

See How ICF Works for a more detailed description of inertial confinement fusion.

Recipe for a Small Star

- Take a hollow, spherical plastic capsule about two millimeters in diameter (about the size of a small pea)

- Fill it with 150 micrograms (less than one-millionth of a pound) of a mixture of deuterium and tritium, the two heavy isotopes of hydrogen.

- Take a laser that for about 20 billionths of a second can generate 500 trillion watts—the equivalent of five million million 100-watt light bulbs.

- Focus all that laser power onto the surface of the capsule.

- Wait ten billionths of a second.

- Result: one miniature star.

By following our recipe, we would make a miniature star that lasts for a tiny fraction of a second. During its brief lifetime, it will produce energy the way the stars and the sun do, by nuclear fusion. Our little star will produce ten to 100 times more energy than we used to ignite it.

How ICF Works

When the 20-beam Shiva laser was completed in 1978, it was the world's most powerful laser. It delivered more than ten kilojoules of energy in less than a billionth of a second in its first full-power firing. About the size of a football field, Shiva was the latest in a series of laser systems built over two decades, each five to ten times more powerful than its predecessor.

When the 20-beam Shiva laser was completed in 1978, it was the world's most powerful laser. It delivered more than ten kilojoules of energy in less than a billionth of a second in its first full-power firing. About the size of a football field, Shiva was the latest in a series of laser systems built over two decades, each five to ten times more powerful than its predecessor. Since the late 1940's, researchers have used magnetic fields to confine hot, turbulent mixtures of ions and free electrons called plasmas so they can be heated to temperatures of 100 to 300 million kelvins (180 million to 540 million degrees Fahrenheit). Under those conditions, positively charged deuterium nuclei (containing one neutron and one proton) and tritium nuclei (two neutrons and one proton) can overcome the repulsive electrostatic force that keeps them apart and "fuse" into a new, heavier helium nucleus with two neutrons and two protons. The helium nucleus has a slightly smaller mass than the sum of the masses of the two hydrogen nuclei, and the difference in mass is released as kinetic energy according to Albert Einstein's famous formula E=mc². The energy is converted to heat as the helium nucleus, also called an alpha particle, and the extra neutrons interact with the material around them.

In the 1970's, scientists began experimenting with powerful laser beams to compress and heat the hydrogen isotopes to the point of fusion, a technique called inertial confinement fusion, or ICF. In the "direct drive" approach to ICF, powerful beams of laser light are focused on a small spherical pellet containing micrograms of deuterium and tritium. The rapid heating caused by the laser "driver" makes the outer layer of the target explode. In keeping with Isaac Newton's Third Law ("For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction"), the remaining portion of the target is driven inwards in a rocket-like implosion, causing compression of the fuel inside the capsule and the formation of a shock wave, which further heats the fuel in the very center and results in a self-sustaining burn known as ignition. The fusion burn propagates outward through the cooler, outer regions of the capsule much more rapidly than the capsule can expand. Instead of magnetic fields, the plasma is confined by the inertia of its own mass – thus the term inertial confinement fusion.

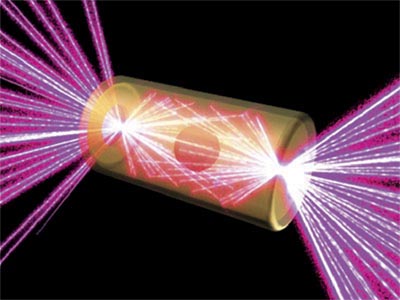

In the "indirect drive" method, the approach to be attempted first at NIF, the lasers heat the inner walls of a gold cavity called a hohlraum containing the pellet, creating a superhot plasma which radiates a uniform "bath" of soft X-rays. The X-rays rapidly heat the outer surface of the fuel pellet, causing a high-speed ablation, or "blowoff," of the surface material and imploding the fuel capsule in the same way as if it had been hit with the lasers directly. Symmetrically compressing the capsule with radiation forms a central "hot spot" where fusion processes set in – the plasma ignites and the compressed fuel burns before it can disassemble.

NIF will be the first laser in which the energy released from the fusion fuel will exceed the laser energy used to produce the fusion reaction. Unlocking the stored energy of atomic nuclei will produce ten to 100 times the amount of energy required to initiate the self-sustaining fusion burn. Creating inertial confinement fusion and energy gain in the NIF target chamber will be a significant step toward making fusion energy viable in commercial power plants (see Inertial Fusion Energy). LLNL scientists also are exploring other approaches to developing ICF as a commercially viable energy source (see Fast Ignition).

Because modern thermonuclear weapons use the fusion reaction to generate their immense energy, scientists will use NIF ignition experiments to examine the conditions associated with the inner workings of nuclear weapons (see Stockpile Stewardship). Ignition experiments can also be used to help scientists better understand the hot, dense interiors of large planets, stars and other astrophysical phenomena (see Science at the Extremes).

More Information

J.D. Lindl, "Development of the indirect-drive approach to inertial confinement fusion and the target physics basis for ignition and gain," Physics of Plasmas, Vol. 2, November 1995, pp. 3933-4024 (PDF)"Inertial Confinement Fusion: The Quest for Ignition and Energy Gain Using Indirect Drive" (book review)

Plasma Physics and ICF

Minimizing laser-plasma instabilities in the NIF hohlraum is a key to achieving ignition.

Minimizing laser-plasma instabilities in the NIF hohlraum is a key to achieving ignition. The conditions of the plasma formed by the X-rays from the hohlraum and the material inside it are crucial to achieving ignition.

For ignition to occur, accurate measurements of the density and temperature of the plasma inside the hohlraum, as well as the conditions of the fusion capsule itself, are essential. At NIF, plasma physicists have developed novel diagnostic techniques based on active probing by optical light or X-ray scattering (see Diagnostics). Knowledge of the hohlraum plasma temperatures and density is then used to predict and model the interaction of the laser beams with the hohlraum plasma and the radiation production where the laser energy is deposited at the hohlraum wall. Plasmas are known to interact with lasers through acoustic and electrodynamic waves that can be driven to instabilities, reflecting large fractions of the light. In addition, the laser beams can filament – that is, break up, refract, diffract and transfer energy among each other (see Laser-Plasma Interactions). The goal is to determine the onset for these processes through experiments and modeling, and to choose hohlraums for NIF that efficiently achieve the required radiation conditions (see Target Fabrication).

Data from first experiments on the NIF, done early on in the construction of the facility with just four of the 192 beams, successfully demonstrated that beam propagation can be achieved over the plasma-scale length of an ignition-size hohlraum (see NIF Early Light). This was achieved by applying laser beam smoothing techniques that remove high-intensity speckles, or hot spots, in the laser beam where instabilities first develop. Extensive supercomputer modeling has been subsequently applied, and the propagation of the beams and the observed threshold behavior for the onset of instabilities and laser beam break-up is now understood (see Target Physics). These studies will be continued on NIF when half of the beams are available for experiments to optimize the laser beam intensities and hohlraum materials for ignition experiments.

More Information

"Simulations of early experiments show laser project is on track," Newsline, Sept. 21, 2007 (PDF)"Experiments and multiscale simulations of laser propagation through ignition-scale plasmas," Nature Physics, Sept. 2, 2007 (Subscription required)

How ICF Works

ReplyDeleteHow ICF Works|Plasma Physics & ICF

When the 20-beam Shiva laser was completed in 1978, it was the world's most powerful laser. It delivered more than ten kilojoules of energy in less than a billionth of a second in its first full-power firing. About the size of a football field, Shiva was the latest in a series of laser systems built over two decades, each five to ten times more powerful than its predecessor.

Since the late 1940's, researchers have used magnetic fields to confine hot, turbulent mixtures of ions and free electrons called plasmas so they can be heated to temperatures of 100 to 300 million kelvins (180 million to 540 million degrees Fahrenheit). Under those conditions, positively charged deuterium nuclei (containing one neutron and one proton) and tritium nuclei (two neutrons and one proton) can overcome the repulsive electrostatic force that keeps them apart and "fuse" into a new, heavier helium nucleus with two neutrons and two protons. The helium nucleus has a slightly smaller mass than the sum of the masses of the two hydrogen nuclei, and the difference in mass is released as kinetic energy according to Albert Einstein's famous formula E=mc². The energy is converted to heat as the helium nucleus, also called an alpha particle, and the extra neutrons interact with the material around them.

In the 1970's, scientists began experimenting with powerful laser beams to compress and heat the hydrogen isotopes to the point of fusion, a technique called inertial confinement fusion, or ICF. In the "direct drive" approach to ICF, powerful beams of laser light are focused on a small spherical pellet containing micrograms of deuterium and tritium. The rapid heating caused by the laser "driver" makes the outer layer of the target explode. In keeping with Isaac Newton's Third Law ("For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction"), the remaining portion of the target is driven inwards in a rocket-like implosion, causing compression of the fuel inside the capsule and the formation of a shock wave, which further heats the fuel in the very center and results in a self-sustaining burn known as ignition. The fusion burn propagates outward through the cooler, outer regions of the capsule much more rapidly than the capsule can expand. Instead of magnetic fields, the plasma is confined by the inertia of its own mass – thus the term inertial confinement fusion.

In the "indirect drive" method, the approach to be attempted first at NIF, the lasers heat the inner walls of a gold cavity called a hohlraum containing the pellet, creating a superhot plasma which radiates a uniform "bath" of soft X-rays. The X-rays rapidly heat the outer surface of the fuel pellet, causing a high-speed ablation, or "blowoff," of the surface material and imploding the fuel capsule in the same way as if it had been hit with the lasers directly. Symmetrically compressing the capsule with radiation forms a central "hot spot" where fusion processes set in – the plasma ignites and the compressed fuel burns before it can disassemble.

NIF will be the first laser in which the energy released from the fusion fuel will exceed the laser energy used to produce the fusion reaction. Unlocking the stored energy of atomic nuclei will produce ten to 100 times the amount of energy required to initiate the self-sustaining fusion burn. Creating inertial confinement fusion and energy gain in the NIF target chamber will be a significant step toward making fusion energy viable in commercial power plants (see Inertial Fusion Energy). LLNL scientists also are exploring other approaches to developing ICF as a commercially viable energy source (see Fast Ignition).

Because modern thermonuclear weapons use the fusion reaction to generate their immense energy, scientists will use NIF ignition experiments to examine the conditions associated with the inner workings of nuclear weapons (see Stockpile Stewardship). Ignition experiments can also be used to help scientists better understand the hot, dense interiors of large planets, stars and other astrophysical phenomena (see Science at the Extremes).

ReplyDeleteMore Information

J.D. Lindl, "Development of the indirect-drive approach to inertial confinement fusion and the target physics basis for ignition and gain," Physics of Plasmas, Vol. 2, November 1995, pp. 3933-4024 (PDF)

"Inertial Confinement Fusion: The Quest for Ignition and Energy Gain Using Indirect Drive" (book review)