Industry and Market Structure

Source: NGSA

The natural gas industry is an extremely important segment of the U.S. economy. In addition to providing one of the cleanest burning fuels available to all segments of the economy, the industry itself provides much valuable commerce to the U.S. economy. Below is a brief description of the structure of the natural gas industry and market, as well as links to information on the make-up of the various segments of the natural gas industry, and recent statistics regarding the supply of natural gas. To learn about the processes associated with the natural gas supply chain, click here.

To jump ahead to specific topics in this section, click on the links below:

Overview of Industry Structure - discusses how different market participants interact to bring supplies of natural gas to the market.

Industry Makeup - discusses the composition of the industry.

Natural Gas Market Overview - discusses the natural gas market, and the forces that affect the interaction of supply and demand for natural gas .

Market Activity -provides a snapshot of recent wholesale market activity as reported by various indices and platforms.

Overview of Industry Structure

The structure of the natural gas industry has changed dramatically since the mid-1980's. In the past, the structure of the natural gas industry was simple, with limited flexibility and few options for natural gas delivery. Exploration and production companies explored and drilled for natural gas, selling their product at the wellhead to large transportation pipelines. These pipelines transported the natural gas, selling it to local distribution utilities, who in turn distributed and sold that gas to its customers. The prices for which producers could sell natural gas to transportation pipelines was federally regulated, as was the price at which pipelines could sell to local distribution companies. State regulation monitored the price at which local distribution companies could sell natural gas to their customers.

Getting Natural Gas to Market - Prior to Deregulation and Pipeline Unbundling

Source: NGSA

Thus, the structure of the natural gas industry prior to deregulation and pipeline unbundling was very straightforward. However, with regulation of wellhead prices, as well as assured monopolies for large transportation pipelines and distribution companies, there was little competition in the marketplace, and incentives to improve service and innovate were few. Regulation of the industry also led to natural gas shortages in the 1970s, and surpluses in the 1980s. To review the history of natural gas regulation, click here.

The natural gas industry today has changed dramatically, and is much more open to competition and choice. Wellhead prices are no longer regulated; meaning the price of natural gas is dependent on supply and demand interactions. Interstate pipelines no longer take ownership of the natural gas commodity; instead they offer only the transportation component, which is still under federal regulation. LDCs continue to offer bundled products to their customers, although retail unbundling taking place in many states allows the use of their distribution network for the transportation component alone. End users may purchase natural gas directly from producers or LDCs.

One of the primary differences in the current structure of the market is the existence of natural gas marketers. Marketers serve to facilitate the movement of natural gas from the producer to the end user. Essentially, marketers can serve as a middle-man between any two parties, and can offer either bundled or unbundled service to its customers. Thus, in the structure mentioned above, marketers may be present between any two parties to facilitate the sale or purchase of natural gas, and can also contract for transportation and storage. Marketers may own the natural gas being transferred, or may simply facilitate its transportation and storage. Essentially, a myriad of different ownership pathways exist for natural gas to proceed from producer to end user.

Simplified Structure of Industry after Pipeline Unbundling

Source: NGSA

The diagram shows a simplified representation of the structure of the natural gas industry after pipeline unbundling and wellhead price deregulation. It is important to note that the actual ownership pathway of the gas may be significantly more complicated, as the marketer or the LDC are not the final users. Either of these two entities may sell directly to the end user, or to other marketers or LDCs.

The regulatory environment of the day has a dramatic effect on shaping the structure of the industry. To learn more about the current regulatory environment for the natural gas industry, click here.

The actions of the federal government and its related agencies and departments can also have a significant impact on the structure and functioning of the natural gas industry. To learn more about how government actions can affect the natural gas industry, click here.

Source: NGSA

Industry Makeup

Now that the basic structure of the natural gas industry has been discussed, it is possible to examine the business characteristics and relevant statistics of each industry segment.

An excellent source for statistics and information on the natural gas industry and its various sectors is the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA was created in 1977 as the statistical arm of the Department of Energy, charged with developing energy data and analyses that help to enhance the understanding of the energy industry. Click here to view the EIA's homepage. For a good overview of relevant updated statistics related to the natural gas industry, view the EIA's summary statistics on natural gas here.

Below are some statistics (based on EIA data for the year 2007) on the makeup of the natural gas industry. Follow the links to view the most up to date information on each sector:

Producers - There are over 6,300 producers of natural gas in the United States. These companies range from large integrated producers with worldwide operations and interests in all segments of the oil and gas industry, to small one or two person operations that may only have partial interest in a single well. The largest integrated production companies are termed 'Majors', of which there are 21 active in the United States. For more information on the production of natural gas in the United States, click here. Information on the production of natural gas is also available on EIA's website here.

Processing - There are over 530 natural gas processing plants in the United States, which were responsible for processing almost 15 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and extracting over 630 million barrels of natural gas liquids in 2006. For more information on natural gas processing, visit the Gas Processors Association here. For updated statistics on the processing of natural gas in the United States, click here.

Pipelines - There are about 160 pipeline companies in the United States, operating over 300,000 miles of pipe. Of this, 180,000 miles consist of interstate pipelines. This pipeline capacity is capable of transporting over 148 Billion cubic feet (Bcf) of gas per day from producing regions to consuming regions. For more information on the natural gas pipeline infrastructure in the United States, click here. To see a list of major pipeline companies, including links to their websites, visit the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's website here.

Storage - There are about 123 natural gas storage operators in the United States, which control approximately 400 underground storage facilities. These facilities have a storage capacity of 4,059 Bcf of natural gas, and an average daily deliverability of 85 Bcf per day. The EIA maintains a weekly storage survey, monitoring the injection and withdrawal of stored natural gas. This survey gives a good indication of the status of the natural gas market, measuring the natural gas that is extracted or stored at any one time in response to the demand for natural gas. To learn more about this survey, visit the EIA here. To view more statistics and information related to natural gas storage in the United States, click here.

Marketing - The status of the natural gas marketing segment of the industry is constantly changing, as companies enter and exit from the industry quite frequently. As of 2000, there were over 260 companies involved in the marketing of natural gas. In this same year, about 80 percent of all the natural gas supplied and consumed in North America passed through the hands of natural gas marketers. The volume of non-physical natural gas that passes through the hands of marketers is very large, and can be much greater than the actual physical volume consumed. This is an indication of vibrant, transparent commodity markets for natural gas. For instance, in 1998, it is estimated that for every thousand cubic feet of natural gas consumed, about 2.7 thousand cubic feet passed through natural gas marketers. For more information on natural gas and energy marketers, visit the National Energy Marketers Association here.

Local Distribution Companies - There are about 1,200 natural gas distribution companies in the U.S., with ownership of over 1.2 million miles of distribution pipe. While many of these companies maintain monopoly status over their distribution region, many states are currently in the process of offering consumer choice options with respect to their natural gas distribution. To learn about the status of distribution restructuring across the United States visit the EIA here. To learn more about natural gas distribution companies and their regulatory structure, visit the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners here. The American Gas Association is also an excellent source for information on LDCs.

Natural Gas Market Overview

The nature of the natural gas market is similar to other competitive commodity markets: prices reflect the ability of supply to meet demand at any one time. The economics of producing natural gas are relatively straightforward. Like any other commodity, the price of natural gas is largely a function of demand and the supply of the product.

Natural Gas Volatility and Price Levels at Henry Hub

Source: Energy Information Administration, Office of Oil and Gas;

based on Natural Gas Monthly publications

When demand for gas is rising, and prices rise accordingly, producers will respond by increasing their exploration and production capabilities. As a consequence, production will over time tend to increase to match the stronger demand. However, unlike many products, where production can be increased and sustained in a matter of hours or days, increases in natural gas production involve much longer lead times. It takes time to acquire leases, secure required government permits, do exploratory seismic work, drill wells and connect wells to pipelines; this can take as little as 6 months, and in some cases up to ten years. There is also uncertainty about the geologic productivity of existing wells and planned new wells. Existing wells will naturally decline at some point of their productive life and the production profile over time is not known with certainty. Thus, it takes time to adjust supplies in the face of increasing demand and rising prices. To learn more about factors that affect the supply of natural gas, click here.

The supply response to prices was demonstrated emphatically following the winter of 2000-2001 as producers substantially increased production investments and activities in response to higher prices. Likewise higher prices (and the U.S. recession) also reduced demand for natural gas. The supply and demand responses led to a new equilibrium in 2002 between supply and demand at market clearing prices far below the 2000-2001 peak.

Source: NGSA

In an environment of falling gas prices, the converse will be true. Producers will respond to lower natural gas prices over time by reducing their expenditures for new exploration and production. Production decline in existing wells will decrease productive capacity. At the same time, the lower prices will increase the demand for natural gas. This, in turn, will ultimately result in upward pressure on gas prices. This relationship between changes in the price of natural gas and variations in the supply of and demand for natural gas is sometimes referred to as the "natural gas market cycle."

In the short term, and in relation to existing producing wells, the supply of natural gas is relatively inelastic in response to changes in the price of natural gas. Contrary to some views, producers do not routinely shut in wells when natural gas prices are low. There are several economic drivers that provide an incentive for producers to continue producing even in the face of lower prices.

First, if production is halted from a natural gas well it may not be possible to restore the well's production due to reservoir and wellbore characteristics.

Second, the net present value of recapturing production in the future may be negative relative to producing the gas today -- i.e., it may be better to produce gas today than to wait until the future to produce the gas. If a producer chooses not to operate a well, the lost production cannot be recovered the next month but is instead is deferred potentially years in the future. There are no guarantees that the prices for gas in the future are going to be higher than prices today.

Third, some gas is produced in association with oil, and in order to stop the flow of natural gas, the oil production must be stopped as well, which may not be economic.

Finally, a producer may be financially or contractually bound to produce specific volumes of natural gas.

Producers and consumers react rationally to changes in prices. Fluctuations in gas prices and production levels are a normal response of the competitive and liquid North America gas market. While the price of the natural gas commodity fluctuates, it is this inherent volatility that provides the signals (and incentives) to both suppliers and consumers to ensure a constant move towards supply and demand equality.

Because the natural gas market is so heavily dependent on the interaction of supply and demand, it is important to have knowledge of the factors that affect these two components. To learn more about the supply and demand of natural gas in the United States, click on the links below:

Natural Gas Demand

Natural Gas Supply

To learn more about natural gas as a commodity, click here.

To learn more about the pricing of natural gas in competitive markets, visit the International Energy Agency here.

Energy Sources

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Fusion Energy - Plasma Physics

Plasma Physics

Almost all of the observable matter in the universe is in the plasma state. Formed at high temperatures when electrons are stripped from neutral atoms, plasmas consist of freely moving ions and free electrons. They are often called the "fourth state of matter" because their unique physical properties distinguish them from solids, liquids and gases. Characteristics of typical plasmas

Characteristics of typical plasmas Plasma densities and temperatures vary widely, from the cold gases of interstellar space to the extraordinarily hot, dense cores of stars and inside a nuclear weapon. On one end of the spectrum, plasma physicists study conditions of high vacuum, with only a few particles in a volume of one cubic centimeter – about the volume of a sugar cube. On the other end of the density range, plasmas with densities sometimes well above 1,000 times the density of a solid occur in stellar interiors and in laboratory experiments that attempt to reproduce the processes in the sun. Although we now most commonly encounter plasmas in energy-efficient light bulbs, plasmas may hold their greatest potential as a future inexhaustible source of energy (see Inertial Fusion Energy).

Two areas of plasma physics have been addressed with experiments using high-energy lasers and both are very relevant to the attempt to create inertial fusion (see How to Make a Star). First are studies of the phenomena created by the laser interacting with the plasma. Of particular importance in this area are two mechanisms of laser-plasma coupling: "stimulated Brillouin scattering" and "stimulated Raman scattering," two ways the energy of the laser beam is shared with the plasma (see Laser-Plasma Interactions). Both effects need to be minimized in order to drive the implosion of the ignition capsule as efficiently as possible.

The second area involves attempts to use the laser to emulate other phenomena occurring in nature. This research is also important to inertial fusion, but it extends well beyond that into fundamental areas of science, such as interpenetrating plasmas and plasma flow in a magnetic field.

The capabilities of NIF will allow production of hot dense plasmas that are sufficiently large and homogeneous to allow their detailed characterization, and thus to study these phenomena. NIF will allow measurement of electron and ion temperatures, charge states, electron density and plasma flow velocities, all of which are essential for understanding experiments on the two basic areas of plasma physics described above.

More Information

Basic Research Directions for User Science at the National Ignition Facility, National Nuclear Security Administration and U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, November 2011"Taking on the Stars: Teller´s Contributions to Plasma and Space Physics," Science & Technology Review, July/August 2007

"Duplicating the Plasmas of Distant Stars," Science & Technology Review, April 1999

Perspectives on Plasmas - The Fourth State of Matter

Laser–Plasma Interactions

The coupling of high-intensity laser light to plasmas has been the subject of experimental investigations for many years. Past experiments have focused on measuring a broad range of phenomena, such as resonance and collisional absorption, filamentation, density profile and particle distribution modification, and the growth and saturation of various parametric instabilities. These phenomena depend on both the properties of the laser (such as intensity, wavelength, and pulse length coherence) and the composition of the plasma. NIF's large, uniform plasmas and laser-pulse shaping, coupled to the diagnostics possible on NIF, make it an ideal site for studying these processes with new precision, and with the hope of new insights.Laser–Plasma Instabilities

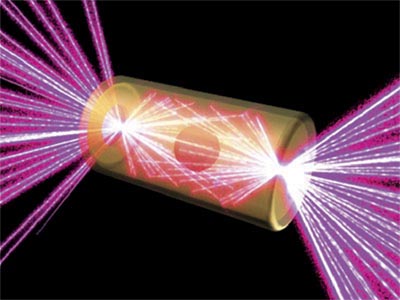

Experimental studies of laser–plasma instabilities have become particularly important in recent years as a result of the vigorous research effort in laser-driven inertial confinement fusion (ICF) (see How to Make a Star). The success of ICF depends partly on mitigating the undesirable effects of two particular parametric instabilities, stimulated Raman scattering and stimulated Brillouin scattering.These two instabilities are of particular importance because both degrade the target compression efficiency in a spherical implosion experiment. Electron Landau damping from the stimulated Raman scattering instability produces fast electrons that can preheat the core of an imploding sphere prior to the arrival of the compression shock front. The stimulated Brillouin scattering instability can scatter a substantial fraction of the incident laser light, causing an overall reduction in the laser-to-X-ray drive efficiency and modifying the X-ray drive symmetry. The 2009–2010 NIF hohlraum energetics shot campaign is yielding useful data for efforts to control and limit scattering instabilities.

Figure 1. Experiments on smaller lasers have shown that multibeam processes can reduce turbulent laser scatter.

Figure 1. Experiments on smaller lasers have shown that multibeam processes can reduce turbulent laser scatter. Filamentation

Another aspect of present and future research involves controlling laser-driven optical turbulence in plasmas; this would allow taming of the potential deleterious effects of multiple high-intensity laser beams interacting in an uncontrolled and unpredictable way with large hohlraum plasmas. Considering that a single laser beam can filament uncontrollably in hot plasma, it may seem hopeless to try to control multiple crossing beams. This is not necessarily the case, however, if appropriate spatial filtering and delayed feedback is introduced into the system. This finding from chaos theory can potentially be converted to the coupled, nonlinear case of high-power, interacting laser beams in plasma. Converting these theoretical insights into practical solutions in a large-scale, well-diagnosed, laser–plasma system is a principle goal in this work.Crucial pieces of the puzzle have been investigated in the past on smaller lasers and simpler systems. On NIF, these pieces are finally being merged together and a strategy for suppressing the instabilities of wide-aperture laser beams is being implemented by promoting multiple crossing beam interactions. Recent (2009–2010) shot series on NIF have demonstrated efficient heating of ignition-scale hohlraums with the radiation temperature and illumination symmetry required for inertial confinement fusion capsule implosions. The hohlraums show 85 percent coupling of the incident laser energy and scale with radiation temperature according to radiation hydrodynamic calculations and modeling. A technique called wavelength tuning was used to great effect in these hohlraum energetics shots. It makes use of the overlap of beams that occurs at each laser entrance hole as beams enter the hohlraum (Figure 2). Tuning the outer and inner beams with respect to one another controls the laser power distribution in the hohlraum by redirecting laser light in the overlapping beam area, allowing the laser to redistribute power to balance heating and produce more symmetrical target compression.

This sort of precision tuning will continue to be a topic of investigation. Very recent numerical simulations are showing that by using three tunable wavelengths between cones of beams on the NIF, rather than two, the energy transfer between beams can be more precisely tuned to redirect the light out of the target regions most prone to backscatter instabilities. It is predicted that using a third wavelength option could significantly reduce stimulated Raman scattering losses and increase the hohlraum radiation drive, while maintaining a good implosion symmetry.

Figure 2. Crossing laser beams in the plasma grating. The tuning technique has been effectively used to redistribute energy deposited on the hohlraum in 2009–2010 NIF experiments.

Figure 2. Crossing laser beams in the plasma grating. The tuning technique has been effectively used to redistribute energy deposited on the hohlraum in 2009–2010 NIF experiments. Laser–Plasma Coupling and HED Physics

In addition to its importance for ICF, high-intensity, laser–plasma coupling presents an extraordinarily rich topic in the study of high-energy-density physics. For example, laser-produced plasmas provide a unique environment for the study of collisional and resonance absorption of laser light. Numerous experiments using various kinds of target materials and widely varying laser parameters have verified the general features of collisional absorption, such as the dependence of absorption on plasma temperature, scale length, laser wavelength, and intensity.Experiments investigating resonance absorption, which occurs at the critical density surface, show an expected dependence on the angle of incidence and polarization of the laser. These experiments, however, also show some discrepancies in the absorbed energy that may be attributed to rippling of the critical density surface. Density profile modification has been observed in experiments where resonance absorption is the dominant coupling mechanism. This profile modification can lead to harmonic generation in back-reflected laser light.

More Information

Symmetric Inertial Confinement Fusion Implosions at ultra-high laser energies, Science, Vol. 327. no. 5970, pp. 1228–1231 (2010) (subscription required)"Targets Designed for Ignition," Science & Technology Review, June 2010

Fusion Energy - Why LIFE: Tackling the Global Energy Crisis

Why LIFE: Tackling the Global Energy Crisis

LIFE will deliver a safe and secure, carbon-free, affordable, sustainable, and enduring supply of baseload electricity to people throughout the world, soon enough to make a difference to our shared future.

Providing for the world's energy demands is one of the most urgent—and difficult—challenges facing our society. Even with likely improvements in efficiency and energy conservation, there is a critical need to rebalance electricity supply away from fossil fuels to ensure long-term sustainability of natural resources, reduce carbon emissions over the next half-century, and stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations thereafter. The projected electrification of transport further increases this need, as does our increasing reliance on products fabricated from the very same natural resources that are currently being burned to create electricity.  Diminishing energy supply (grey) and rapidly accelerating energy demand (green) are producing a window of opportunity for new energy solutions. Rollout from the 2030s requires a focused development solution and an immediate start. Chart assumes that the world population stabilizes at 10 billion, consuming at 2/3 the United States rate from 1985. Renewable sources such as solar, photovoltaic, wind, and hydro will play an essential role in meeting this challenge, but do not have the storage capacity or available land to meet the majority baseload power requirements of most countries. Nuclear energy offers many attractions, but requires addressing the safety and proliferation problems associated with enrichment, reprocessing, and high-level waste storage. While all these solutions could and should be pursued, the need to replace the current fleet of power plants provides a clear window of opportunity to transform the energy landscape from 2030 onwards.

Diminishing energy supply (grey) and rapidly accelerating energy demand (green) are producing a window of opportunity for new energy solutions. Rollout from the 2030s requires a focused development solution and an immediate start. Chart assumes that the world population stabilizes at 10 billion, consuming at 2/3 the United States rate from 1985. Renewable sources such as solar, photovoltaic, wind, and hydro will play an essential role in meeting this challenge, but do not have the storage capacity or available land to meet the majority baseload power requirements of most countries. Nuclear energy offers many attractions, but requires addressing the safety and proliferation problems associated with enrichment, reprocessing, and high-level waste storage. While all these solutions could and should be pursued, the need to replace the current fleet of power plants provides a clear window of opportunity to transform the energy landscape from 2030 onwards.Fueling the Future with LIFE

For 50 years, it has been recognized that fusion energy provides a highly attractive solution to society's demand for safe, secure, environmentally sustainable energy—at a scale that meets our long-term needs. But despite fusion's tantalizing benefits, it has been largely ignored in energy policy discussions because it is viewed as a technology too immature to affect energy production over the next few decades, when it is most needed. Drawing on huge prior investment by the U.S. Department of Energy, and linking with recent innovations in the semiconductor industry, we are now at a stage to change this paradigm and offer a deliverable way forward.Scientific demonstrations by the end of 2012 on the National Ignition Facility will provide the basis for a fleet of LIFE (laser inertial fusion energy) power plants that are being designed to deliver gigawatt-scale electricity—equivalent to the largest coal or nuclear power stations.

"Energy is central to poverty reduction efforts. It is also central to the transition to a sustainable green economy. It affects all the social, economic and environmental aspects of development, including gender inequality, climate change, food security, health and education and overall economic growth."

—United Nations Industrial Development OrganizationLearn more about the National Ignition Facility and its role in demonstrating fusion.

Learn more about the benefits of LIFE.

External view of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) target chamber. NIF will be the first fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and self-sustaining burn, as required for a power station.

External view of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) target chamber. NIF will be the first fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and self-sustaining burn, as required for a power station.Why LIFE: Advantages of the LIFE Approach

The Laser Inertial Fusion Energy (LIFE) approach adopts a power plant design using the physics setup currently being tested on the National Ignition Facility (NIF), coupled to a driver solution using existing manufacturing technology, and a concept of plant operations that overcomes the need to wait for advanced material development. It has been designed to take full advantage of U.S. leadership and prior investment in relevant technologies, such as NIF. This reduces the cost and delay associated with a more conventional approach that requires multiple phased facilities to mitigate the risk arising from unproven physics, use of novel materials, and new technologies.LIFE is being designed as a reasonable extension of NIF and manufacturing industries, with:

The LIFE facility design offers many

attractive features:

Proven design

The LIFE plant design has a similar footprint to NIF while generating enough power for 2.3 million people, at present usage rates. The designs for NIF and LIFE have comparable laser energy, target performance, cost, and operations concepts, such as modular design components.Competitive cost

Estimates of the capital and operational cost of the LIFE approach are competitive with new nuclear plants and other sources of low-carbon baseload electricity. LIFE electricity costs compare favorably with other low-carbon technologies.

LIFE electricity costs compare favorably with other low-carbon technologies. Intrinsic safety

A LIFE plant is intrinsically safe due to the nature of fusion, which requires continuous delivery of laser energy to drive the operation—in contrast to fission, where the reaction can occur without intervention. Runaway reaction or meltdown is simply not possible. No cooling, external power, or active intervention is required from a safety perspective in the event of system shutdown (deliberate or otherwise). There is also no spent fuel; fusion has a closed fuel cycle (for the tritium), with helium gas as the byproduct.Proven physics

Ignition on NIF is anticipated in the 2011–2012 period. Assuming success, NIF ignition will provide direct evidence of the required physics basis for a power plant. Any IFE driver/target design other than one based directly on NIF evidence would almost certainly require a new ignition demonstration facility, since knowledge of driver performance and fusion coupling are demonstrably insufficient to move forward on the basis of computational extrapolations. Using proven physics shortens the timeline and reduces cost.Modular design enables high reliability and availability

NIF's laser beams pass through thousands of line-replaceable units (LRUs)—self-contained packages containing multiple laser components that can be assembled and tested off-line in a clean room, then installed on the laser as a unit—on their way to the target chamber; these units can be individually removed and replaced for maintenance work with substantially no laser downtime. The LIFE approach takes the modular concept a step further. LIFE design accounts for periodic replacement of materials in high-risk environments (due to extreme temperatures, neutron bombardment, etc.) such as final optics without requiring wholesale changes to the rest of the plant.This concept is applied, for example, at the level of laser beam lines, which have been designed with an innovative new architecture to reduce their physical size by over an order of magnitude compared with NIF. A beam box less than 11 meters long has been designed as an LRU. This allows off-site manufacture and maintenance, the ability to deliver a beam box to the construction site on a standard truck, and changeover of individual beamlines while the plant is operational. Even the fusion chamber is split into a set of independent modules that can be withdrawn to a maintenance bay in isolation or as a complete unit. By adopting a design approach that promotes modular, replaceable units throughout the plant, the components of the LIFE plant can sustain economic operations at high availability and reliability, and have the ability to be inspected and maintained.

Use of available materials

The pace of fusion delivery has been driven in large part by the long timescales associated with advanced materials development and their operational certification for high-threat structural components. By adopting the NIF approach of using LRUs across all life-limited areas of the power plant (including the fusion engine itself), quantitative analyses and full system designs show that near-term materials can be used, while maintaining the required plant availability and reliability. In this way, a commercial demonstration plant can be constructed with high confidence, and used to test prospective upgrade materials in a relevant fusion environment.Integrated laser designs have been developed for LIFE that achieve the required performance characteristics using Nd:glass gain media, helium cooling, and diode technology based on current production methods. The mass markets associated with these solid-state components provide a highly competitive supply chain that now quotes diode price points consistent with a commercially viable rollout with no new research and development. Similarly, the use of a known production route for the structural materials of the demonstration plant allows rapid time-to-construction, and is not contingent on the development of a new class of materials.

Low tritium inventory for start-up

Many fusion plant designs require large quantities of tritium for start up and operations (with estimates of 40 to 60 kg per GW power plant, which is high compared with the available global inventory). This substantially reduces the rate of rollout of a fleet and has led some senior researchers to question the fundamental viability of fusion. By virtue of the high fractional burn-up in an IFE capsule (>30% for a LIFE facility), and by adopting a National Ignition Campaign (NIC)-scale fusion target and a phased approach to operations, the start-up tritium inventory can be reduced by an order of magnitude. Breeding from this system can then be used for subsequent steps.Continuous improvement

IFE greatly benefits from its ability to use modular advances in component technologies (e.g., subsystem electrical efficiency) and in enhanced fusion performance. Improvements can thus continuously drive improvements in the overall plant cost and cost of electricity by large factors. Future designs can readily be incorporated as long as they maintain the same interface characteristics to the rest of the plant.

IFE greatly benefits from its ability to use modular advances in component technologies (e.g., subsystem electrical efficiency) and in enhanced fusion performance. Improvements can thus continuously drive improvements in the overall plant cost and cost of electricity by large factors. Future designs can readily be incorporated as long as they maintain the same interface characteristics to the rest of the plant.Delivering LIFE: Fusion Energy Soon Enough

to Make a Difference

LIFE takes a near-term, pragmatic approach to delivery.

Despite fusion's potential benefits for a low-carbon energy economy, the long timescales typically associated with fusion development have excluded it from mainstream energy policy considerations. The laser inertial fusion energy (LIFE) concept is intended to change this paradigm, and deliver laser fusion power stations on a timescale that matters.

Despite fusion's potential benefits for a low-carbon energy economy, the long timescales typically associated with fusion development have excluded it from mainstream energy policy considerations. The laser inertial fusion energy (LIFE) concept is intended to change this paradigm, and deliver laser fusion power stations on a timescale that matters.The LIFE approach is based on the demonstration of fusion ignition at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), and uses a modular approach to ensure high plant availability and to allow evolution to more advanced technologies and materials as they become available. Use of NIF's proven physics platform for the ignition scheme is an essential component of an acceptably low-risk solution.

After ignition on NIF, the “next step” would be a power plant generating hundreds of megawatts of thermal power. Estimates of the technology development program requirements, along with manufacturing and construction timescales, indicate that this plant could be commissioned and operational by the mid 2020s. This first plant is designed to demonstrate all the required technologies and materials certification needed for the subsequent rollout of electric power at commercial power plant levels from the 2030s and onward.

The timeliness requirements for commercial delivery are compelling. Rollout from the 2030s would remove 90 to 140 gigatons of CO2-equivalent carbon emissions by the end of the century (assuming U.S. coal plants are displaced and the doubling time for roll-out is between 5 and 10 years). Delaying rollout by just 10 years removes 30 to 35% of the carbon emission avoidance, which at $100/megaton translates to a net present value of $140 to $260 billion dollars. For inertial fusion energy to achieve its full potential in solving our energy/climate challenges, a focused delivery program is urgently needed.

Modeling of the U.S. grid shows the great need for new energy solutions, but early market entry is essential for fusion energy to be relevant.

Modeling of the U.S. grid shows the great need for new energy solutions, but early market entry is essential for fusion energy to be relevant. A delivery-focused, evidence-based approach has been proposed to allow LIFE power plant rollout on a timescale that meets these policy imperatives and is consistent with industry planning horizons. The system-level development path makes full use of the distributed capability in laser and semiconductor technology, manufacturing and construction industries, nuclear engineering and existing grid infrastructure.

The LIFE design adopts a scheme that is being tested directly on the NIF, and uses a factory-built, modular approach to construction, operations, and maintenance. This provides for high plant availability and reliability, reduced construction costs and timescales, and compatibility with accepted models for power plant operations.

The nature of fusion provides for inherent plant safety and a simplified licensing regime, consistent with performance-based, risk-managed regulation. Material choices provide robust security of supply and allow widespread rollout for global market penetration.

Plant design, delivery planning, and vendor engagement are now at a stage that calls for transition to full-scale project delivery (in anticipation of ignition on the NIF by the end of 2012). Successful execution of the LIFE project strengthens American economic competitiveness and allows the United States to regain a leading position in new energy technology development.

Learn more about LIFE commercialization.

Early market entry for fusion has a big impact, displacing 90 to 140 gigatons of CO2, 3 to 4.5 Yucca Mountains, or 3000 to 4000 tons of plutonium in the United States alone.

Early market entry for fusion has a big impact, displacing 90 to 140 gigatons of CO2, 3 to 4.5 Yucca Mountains, or 3000 to 4000 tons of plutonium in the United States alone.- NIF-like fusion performance

- Market-based, diode-pumped laser technology

- Mass-manufactured target techniques

- A modular design that includes line replaceable units at every stage, including the fusion chamber.

Delivering LIFE: LIFE Commercialization

LIFE commercialization begins with subsystem development and laboratory-based technology demonstrations, and then moves directly to a plant capable of continuous fusion operations. The plant is highly flexible and can be configured to support subscale qualification testing as well as commercial power production. This strategy is enabled by the modular architecture of the design and the fact that the fusion chamber and major laser system components are line-replaceable units.This approach has significant advantages. It avoids the need for an intermediate-step engineering test facility, which is a multi-billion-dollar capital investment. Gaining the approval and funding for a test facility, as well as for the first commercial plant, adds significant programmatic risk. Further, the technology requirements for an engineering test facility are substantially the same as for the first plant. Both require high-average-power operation of the laser, hitting and igniting targets on-the-fly, tritium self-sufficiency, and so on. For LIFE, there is little advantage to an intermediate-step facility.

Perhaps even more importantly, the flexible configuration of the first plant mitigates the risk of technology development concurrent with plant design and construction. For example, testing in NIF may result in a change of the laser energy requirement for the first plant. The modular architecture accommodates this by allowing one to add or subtract beam lines from the laser system, with minimal impact to the overall plant design. Similar flexibility applies to the fusion chamber. One can transition directly to full-scale hardware and power production; however, if warranted, subscale hardware can be qualification tested at reduced fusion power levels prior to full scale testing. The ability to develop technology concurrent with first plant design, without the risk of “building the wrong plant,” significantly reduces time to market and enhances the relevance of fusion energy.

Materials Testing

Many of the components needed for a fusion power plant can be developed and tested in a laboratory setting. Examples include high-average-power lasers, tritium handling systems, and corrosion-resistant materials. However, once ignition has been demonstrated, the critical path to commercial fusion energy is dominated by the need to have a quasi-continuous fusion source to qualify materials and processes needed in a commercial plant. Examples of materials and processes that will need this qualification include on-the-fly fusion target ignition with repeatable fusion yield and final optic survival in fusion environment.Materials and structures need to be exposed to the same thermal and radiation loads as will be experienced in a commercial power plant. In addition, the exposure time must be long enough to simulate one or more system lifetimes, for systems such as the fusion chamber and final optic. This can be done in a full-scale fusion chamber, operating at full commercial plant fusion power level, or in a subscale fusion chamber operating at lower average power. This flexibility to test at multiple scales provides significant risk mitigation and allows initial materials qualification testing at small scale, should regulatory or technical issues mandate.

Once the materials and process qualification is complete, the plant will transition to regular operations, delivering 400 MW of commercial power to the grid.

Electrical generation options for the 2010 to 2100 time frame. (Other than LIFE, all costs are from the Electric Power Research Institute.) If another technology is to be made available in time to include in filling the gap left by retiring coal and nuclear plants, work must begin soon to ensure that a supply chain is ready to produce the plants necessary to impact the market.

Electrical generation options for the 2010 to 2100 time frame. (Other than LIFE, all costs are from the Electric Power Research Institute.) If another technology is to be made available in time to include in filling the gap left by retiring coal and nuclear plants, work must begin soon to ensure that a supply chain is ready to produce the plants necessary to impact the market.

The National Ignition Facility:

Ushering in a New Age for Science

“Every great advance in science has issued from a new audacity of imagination.”Scientists have been working to achieve self-sustaining nuclear fusion and energy gain in the laboratory for more than half a century. Ignition experiments at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) are now bringing that long-sought goal much closer to realization.

—John Dewey

NIF's 192 giant lasers, housed in a ten-story building the size of three football fields, will deliver at least 60 times more energy than any previous laser system. NIF will focus more than one million joules of ultraviolet laser energy on a tiny target in the center of its target chamber—creating conditions similar to those that exist only in the cores of stars and giant planets and inside a nuclear weapon. The resulting fusion reaction will release many times more energy than the laser energy required to initiate the reaction.

Experiments conducted on NIF will make significant contributions to national and global security, could lead to practical fusion energy, and will help the nation maintain its leadership in basic science and technology. The project is a national collaboration among government, academia, and many industrial partners throughout the nation.

Programs in the NIF & Photon Science Directorate draw extensively on expertise from across LLNL, including the Physical and Life Sciences, Engineering, Computation, and Weapons and Complex Integration directorates. This goal is a scientific Grand Challenge that only a national laboratory such as Lawrence Livermore can accomplish.

More Information

Much more information on the NIF & Photon Science Directorate's missions and programs is available on this Website. Here are some links to explore:- The Seven Wonders of NIF—How NIF scientists, engineers, and technicians overcame a series of daunting technical challenges to bring NIF to the verge of success.

- How NIF Works—What goes into creating the world's highest-energy laser system.

- How to Make a Star—Achieving thermonuclear burn in the laboratory.

- Stockpile Stewardship–Helping protect national security by ensuring that the nation's nuclear weapons are safe, secure, and reliable.

- Inertial Fusion Energy—Exploring new pathways to safe, clean, limitless energy.

- Photon Science & Applications—Developing advanced high-power, high-intensity, laser technology and applications.

- Laboratory Astrophysics—Providing new tools to study the cosmos.

- Plasma Physics—Understanding the behavior of turbulent plasmas, the "fourth state of matter."

- People—Get to know some of the people who make NIF and Photon Science possible.

- Education—Learn more about lasers and fusion energy.

More Information

T.M. Anklam et al., “LIFE: The Case for Early Commercialization of Fusion Energy,” Fus. Sci. Tech. 60, 66–71 (2011).M. Dunne et al., “Timely Delivery of Laser Inertial Fusion Energy (LIFE),” Fus. Sci. Tech. 60, 19–27 (2011).

Fusion energy is a safe and sustainable source of power - What is LIFE: Understanding LIFE

What is LIFE: Understanding LIFE

Fusion energy is a safe and sustainable source of power.

What is fusion?

Fusion, the process that powers the sun and the stars, is the reaction in which two atoms of hydrogen combine together to form an atom of helium. In the process some of the mass of the hydrogen is converted into energy. The easiest fusion reaction to make happen is combining the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium to make helium and a neutron. Deuterium is plentifully available in ordinary water. Tritium can be produced by combining the fusion neutron with the abundant light metal lithium. Thus fusion has the potential to be an inexhaustible source of energy.More on fusion.

How can we create fusion?

To make fusion happen, the atoms of hydrogen must be heated to very high temperatures (100 million degrees) so they are ionized (forming a plasma) and have sufficient energy to fuse, and then be held together, or confined, long enough for fusion to occur. The sun and stars do this by gravity. Current approaches on earth are magnetic confinement, where a strong magnetic field holds the ionized atoms together while they are heated by microwaves or other energy sources, and inertial confinement, where a tiny pellet of frozen hydrogen is compressed and heated by an intense energy beam, such as a laser, so quickly that fusion occurs before the atoms can fly apart. Laser Inertial Fusion Energy, or LIFE, power plants, as the name suggests, will use the inertial confinement approach.

To make fusion happen, the atoms of hydrogen must be heated to very high temperatures (100 million degrees) so they are ionized (forming a plasma) and have sufficient energy to fuse, and then be held together, or confined, long enough for fusion to occur. The sun and stars do this by gravity. Current approaches on earth are magnetic confinement, where a strong magnetic field holds the ionized atoms together while they are heated by microwaves or other energy sources, and inertial confinement, where a tiny pellet of frozen hydrogen is compressed and heated by an intense energy beam, such as a laser, so quickly that fusion occurs before the atoms can fly apart. Laser Inertial Fusion Energy, or LIFE, power plants, as the name suggests, will use the inertial confinement approach.How does laser fusion power generation work?

A laser fusion power plant operates conceptually like a car engine: fuel is injected (in the form of a small capsule of hydrogen isotopes); a piston is then used to compress and heat the fuel to the point of ignition (with the piston being a large laser); and finally, the spent fuel is exhausted, and the cycle repeats. Repetition rates of up to 15 times a second (similar to an idling car engine) are sufficient to produce a gigawatt of electrical power from an inertial fusion energy plant.More on laser fusion power plants.

Why fusion?

Fusion energy offers the promise of abundant, truly sustainable energy. One out of every 6500 atoms of hydrogen in ordinary water is deuterium, giving a cup of water the energy content of close to 19 gallons of gasoline. In addition, fusion would be environmentally friendly, producing no combustion products or greenhouse gases. While fusion is a process that occurs in the nucleus of an atom, the products of the fusion reaction (helium and a neutron) are not radioactive, and with proper design a fusion power plant would be passively safe, and would produce no long-lived radioactive waste. Fusion has high energy efficiency and so makes efficient use of land resources compared with wind and solar energy. Design studies show that electricity from fusion can be cost competitive with other energy sources. Despite these compelling advantages, the promise of fusion energy remains unfulfilled. Chief among the reasons for this is the simple fact that controlled fusion gain—that is, fusion where more energy results from the reaction that was put into the reaction—has not yet been demonstrated in the laboratory. Without demonstration of scientific feasibility, it is virtually impossible to attract the funding needed to commence serious technology development.

Despite these compelling advantages, the promise of fusion energy remains unfulfilled. Chief among the reasons for this is the simple fact that controlled fusion gain—that is, fusion where more energy results from the reaction that was put into the reaction—has not yet been demonstrated in the laboratory. Without demonstration of scientific feasibility, it is virtually impossible to attract the funding needed to commence serious technology development.What is the LIFE approach?

Fusion energy is reaching a turning point, as the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is poised to demonstrate fusion with energy gain, or ignition, by 2012. Ignition will resolve the question of whether fusion energy is possible. This clears the way for the engineering and technology work needed to establish commercial feasibility. The LIFE effort takes the next step, providing a blueprint on progressing from scientific feasibility to commercial fusion energy in a time frame that is relevant to satisfying the world's ever increasing need for abundant, sustainable energy.The LIFE approach builds upon the technology advances achieved in building and conducting ignition experiments on NIF. Adopting a modular design and construction, building on proven physics and laser technology, and pursuing concurrent integration of required technologies, a LIFE power plant will offer safe, cost-effective, and reliable baseload power.

More on the LIFE power plant design.

Why now?

- NIF ignition will provide the scientific basis for a fusion power plant (for the first time in 50 years)

- Required delivery of safe, carbon-free base load power from the 2020s requires an immediate start on a first-of-its kind plant

- Recent progress in solid-state laser technology has dramatically lowered the cost and size to acceptable levels, removing long-standing obstacles

- Using lessons learned from NIF, the concept of line replaceable units has enabled a fundamentally new approach to power plant design, ensuring high plant availability

- Taken together, a plant with high availability and reliability is now achievable, consistent with the highest level utility requirements for commercial operation

More on delivering LIFE soon enough to make a difference.

The LIFE solution uses:

- Proven physics: demonstrated on the National Ignition Facility

- Available materials: enabling construction of the first plant in the near term

- Market-based technology: using the U.S. solid state (semiconductor) manufacturing base

“I do believe we will be able to solve the energy problem. Energy may well be the problem of the age. And what is the solution? Bringing the Sun to Earth.”

—Dr. Edward Moses, director of the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

—Dr. Edward Moses, director of the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Advantages of Fusion

- Abundant fuel supply

- No risk of runaway reaction

- No greenhouse gas emissions

- No high-level nuclear waste

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory 7000 East Avenue Livermore, CA 94550

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory 7000 East Avenue Livermore, CA 94550How Inertial Fusion Power Plants Work

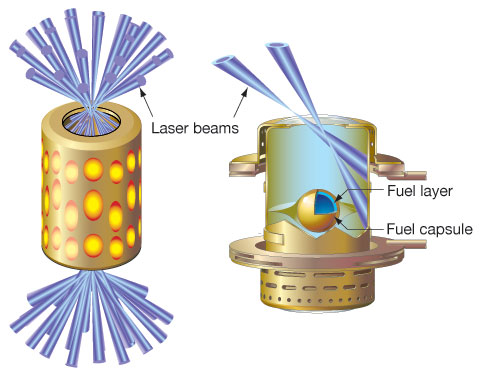

An inertial fusion energy (IFE) power plant consists of a target production facility (or target factory), target injection and tracking systems, the laser, a fusion chamber, and a power conversion system.In the plant, many (typically 10–20) pulses of fusion energy per second would heat a low-activation coolant, surrounding the fusion targets. The coolant in turn would transfer the fusion heat to a turbine and generator to produce electricity.

A laser inertial fusion energy power plant consists of a target production facility (or target factory), laser, fusion chamber, power conversion system, and target injection and tracking systems. Among the factors scientists must consider when developing designs for an IFE plant are:

A laser inertial fusion energy power plant consists of a target production facility (or target factory), laser, fusion chamber, power conversion system, and target injection and tracking systems. Among the factors scientists must consider when developing designs for an IFE plant are:Target Performance

For IFE, energy gain—the ratio of fusion energy from the fusion target divided by laser energy input—between 50 and 100 is needed in order to minimize the portion of generated electric power that has to be recirculated within the plant to operate the laser. A high recirculating power fraction means there is less power available for sale, so the cost of electricity will be higher.Target Factory

The target factory must produce a continuous supply of high-quality targets at an acceptable cost—typically about one million targets per day at around 25¢ per target. The costs of the materials in the target are only a few cents, with the majority cost arising from the production equipment and labor—as with most other mass-manufactured products. Detailed conceptual design studies for IFE target factories have been completed by LLNL and General Atomics.For IFE targets, deuterium–tritium (DT) fusion fuel is contained in a spherical fuel capsule, held at low temperature so that it forms a layer of DT ice on the capsule’s inner surface. The capsules are made of carbon, beryllium, or carbon–hydrogen polymers.

Target Injection and Tracking

Targets will be injected at speeds greater than 100 meters a second and tracked in flight to provide data to a real-time beam-pointing system needed to assure the precise illumination required to achieve ignition and high energy gain. Target injection experiments using gas guns have been conducted at General Atomics, and tracking and engagement studies are underway. The required accuracy appears consistent with the use of existing technology and acousto-optic deflection technology to steer the laser beams onto the target.High-Repetition-Rate Laser

A key component of a laser IFE power plant is the laser. While the total energy of the laser is likely to be comparable to, or even less than that of the National Ignition Facility, the IFE laser must operate at 10–20 shots a second, depending on the target yield per shot and the desired electric output of the power plant. In addition to the ability to operate at high repetition rates, key considerations for the IFE laser include high efficiency (preferably greater than 10%), low cost (to keep the cost of electricity competitive with other energy options), long-life optics, high reliability, and low maintenance costs. The fusion chamber at the National Ignition Facility.

The fusion chamber at the National Ignition Facility. Fusion Chamber

Each fusion target releases a burst of fusion energy in the form of high-energy (14-million-electron-volt) neutrons (about 70% of the energy), x rays, and energetic ions. The fusion chamber includes a meter-thick region that contains lithium (as a liquid metal, molten salt, or solid compound). This serves two purposes. Firstly, it absorbs the fusion output energy, heating up to about 600 degrees Celsius. A heat exchanger is then used to drive a super-critical steam turbine cycle to produce the electricity.Secondly, this lithium “blanket” produces tritium through reactions with the fusion neutrons. This allows a closed fuel cycle to be formed—in which the power plant itself produces a key component of its own fuel. The other part of the fuel, deuterium, is extracted from seawater (roughly one part in 6700). The deuterium found in just 45 liters of water, combined with the amount of lithium found in a single laptop battery would (allowing for inefficiencies) produce 200,000 kW hours (roughly 20–30 years' worth of electricity for someone living in Europe or the United States).

One key issue for the chamber is the survival of the innermost wall (first wall) that is exposed to intense heat and radiation from the target's x rays, ions, and neutrons. Another key issue for the fusion chamber is intra-shot recovery: the conditions inside the chamber (such as vapor and droplet density) that must be recovered between each shot to the point that the next target can be injected and the laser beams can propagate through the chamber to the target.

IFE power plants can use liquid-protected walls for long life, low radioactivity, and low maintenance.

IFE power plants can use liquid-protected walls for long life, low radioactivity, and low maintenance. Power Conversion System

By flowing a coolant through the fusion chamber at a steady rate, the pulsed fusion energy can be extracted at a constant rate and delivered to the power conversion system, which converts the thermal power to electric power. When liquids such as lithium metal or molten lithium salts are used for tritium breeding, the liquid is generally circulated as the primary coolant for the fusion chamber. When solid breeders such as lithium–aluminate (LiAl02) are used, high-pressure helium serves as the chamber coolant.In either case, the primary coolant circulates through heat exchangers that power electric power equipment. The efficiency of the power conversion systems depends on the outlet temperature of the primary coolant, which is limited by the materials used in the construction of the chamber. Conversion efficiencies of 40–50% are now available for the temperatures produced from fusion—using technology developed for modern coal plants. Some work has also been done on ideas for converting a portion of the target energy output directly to electricity.

Separability and Integration

An advantage of IFE is that the subsystems described above can be developed and tested separately and often at lower cost than fully integrated facilities. The IFE power plant, however, requires successful integration of all the components with careful attention to the interfaces and the impact of design choices for one system on the others.Safety and Environment

Inherent safety and environmental sustainability are key benefits of fusion. Key characteristics include:- The source term disappears when the system is off or suspends operations. This is in contrast to a fission reactor, where nuclear reactions are sustained for an extended period.

- Runaway reaction or meltdown is simply not possible. The system contains only tiny amounts of fuel (milligrams) at any point in time, and is only “on” for a billionth of a second per second (equivalent to a small fraction of a second per year).

- No cooling, external power, or active intervention is required in the event of system shutdown (deliberate or otherwise). This is because the residual decay heat is low (at the few-MW level), with no need for external cooling. Upon system shutdown, the engine can be simply left standing—with or without the presence of its coolant.

- No spent fuel, and no requirement for geological storage of radioactive waste. The byproduct of fusion is helium gas.

- IFE plants are designed with a low and segregated tritium inventory, and low activation materials—at levels that can have no offsite consequences either during normal operations or during an accident.

- The consequence of a “design basis accident”’ would be suspension of operations and possibly fire. Electricity would cease to be produced, but there would be no offsite impact.

- The consequences of accidents significantly beyond the design basis are well within the regulatory limits, and represent a paradigm change from the dangers posed by nuclear power or gas transmission pipelines.

More Information

Igniting Our Energy Future,Science & Technology Review, July/August 2011

Safe and Sustainable Energy with LIFE,

Science & Technology Review, April/May 2009

Taking Lasers Beyond the National Ignition Facility, Science & Technology Review, September 1996

Fusion Power Associates

The standard joke about fusion is that it is 50 years away and always will be. The National Ignition Facility (NIF) is on the brink of changing this—with a plan to deliver fusion with net energy gain (more fusion energy out than the laser puts in), or ignition, by the end of 2012.

Located at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California and fully operational since 2009, NIF—the world's largest and most energetic laser—aims to fuse the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium in order to demonstrate the feasibility of laser-based fusion for energy production.

These hydrogen isotopes will be contained within a tiny sphere, which will be placed in the center of a centimeter-long hollow gold cylinder, known as a hohlraum. NIF's 192 laser beams will heat the inside of the hohlraum, generating x rays that cause the fuel sphere to explode and, due to momentum conservation, the deuterium and tritium to rapidly compress. A shockwave from the explosion will then increase the temperature of the compressed matter to the point where the nuclei overcome their mutual repulsion and fuse.

The resulting fusion reaction will release many times more energy than the laser energy required to initiate the reaction.

On the Path to Fusion Ignition

Documented in a pair of papers published in early 2011, NIF physicists have demonstrated—by combining computer simulations and experiments using plastic spheres containing helium, rather than actual fuel pellets, for ease of analysis—that they can achieve the temperature and compression conditions necessary for a self-sustaining fusion reaction, a milestone that they hope to pass before the end of 2012. Target Fabrication Production Manager Beth Dzenitis examines a target designed for NIF experiments.In September 2010, an experiment successfully demonstrated the integration of all the complex systems required for ignition, including the introduction of fusion fuel—deuterium and tritium. This was the first in a series of shots that will lead up to conducting full-scale ignition experiments as part of the National Ignition Campaign.

Target Fabrication Production Manager Beth Dzenitis examines a target designed for NIF experiments.In September 2010, an experiment successfully demonstrated the integration of all the complex systems required for ignition, including the introduction of fusion fuel—deuterium and tritium. This was the first in a series of shots that will lead up to conducting full-scale ignition experiments as part of the National Ignition Campaign. The ongoing National Ignition Campaign is an international effort that includes partners—General Atomics, LLNL, Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories, the University of Rochester Laboratory for Laser Energetics—and collaborators such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, NSTech, the U.K. Atomic Weapons Establishment, and the French Atomic Energy Commission. It is a robust team, with the combined expertise and resources to tackle a scientific challenge never before achieved—fusion with energy gain.

The National Ignition Facility is the proof of principle

for a fusion energy power plant

NIF will be the first fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and self-sustaining burn, as required for a power station. For more information on NIF and updates on NIF experiments, visit the NIF website.for a fusion energy power plant

More Information

S.H. Glenzer et al., “Demonstration of Ignition Radiation Temperatures in Indirect-Drive Inertial Confinement Fusion Hohlraums,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 085004 (2011).J.L. Kline et al., “Observation of High Soft X-Ray Drive in Large-Scale Hohlraums at the National Ignition Facility,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 085003 (2011).

E.I. Moses et al., “The National Ignition Facility and the Promise of Inertial Fusion Energy,” Fus. Sci. Tech. 60, 11–16 (2011).

Fusion Energy - Energy for the Future

Energy for the Future

Harnessing the energy of the sun and stars to meet the Earth's energy needs has been a decades-long scientific and engineering challenge. While a self-sustaining fusion burn has been achieved for

The thermonuclear fusing of hydrogen atoms from water in fusion power plants may someday supply virtually unlimited electricity.brief periods under experimental conditions, the amount of energy that went into creating it was greater than the amount of energy it generated. There was no energy gain, which is essential if fusion energy is ever to supply a continuous stream of electricity. If it is successful, the National Ignition Facility will be the first inertial confinement fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and a self-sustaining fusion burn. In the process, NIF's fusion targets will release 10 to 100 times more energy than the amount of laser energy required to initiate the fusion reaction.

The thermonuclear fusing of hydrogen atoms from water in fusion power plants may someday supply virtually unlimited electricity.brief periods under experimental conditions, the amount of energy that went into creating it was greater than the amount of energy it generated. There was no energy gain, which is essential if fusion energy is ever to supply a continuous stream of electricity. If it is successful, the National Ignition Facility will be the first inertial confinement fusion facility to demonstrate ignition and a self-sustaining fusion burn. In the process, NIF's fusion targets will release 10 to 100 times more energy than the amount of laser energy required to initiate the fusion reaction.target capsule,  a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

A fusion power plant would produce no greenhouse gas emissions, operate continuously to meet demand, and produce shorter-lived and less haza The nuclear power plants in use around the world today utilize fission, or the splitting of heavy atoms such as uranium, to release energy for electricity. A fusion power plant, on the other hand, will generate energy by fusing atoms of deuterium and tritium—two isotopes of hydrogen, the lightest element. Deuterium will be extracted from abundant seawater, and tritium will be produced by the transmutation of lithium, a common element in soil. When the hydrogen nuclei fuse under the intense temperatures and pressures in the NIF rdous radioactive byproducts than current fission power plants. A fusion power plant would also present no danger of a meltdown. a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.

a helium nucleus is formed and a small amount of mass lost in the reaction is converted to a large amount of energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2.Because nuclear fusion offers the potential for virtually unlimited safe and environmentally benign energy, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has made fusion a key element in the nation's long-term energy plans.

The goal of the National Ignition Facility is to achieve fusion by compressing and heating a pea-sized capsule containing a mixture of deuterium and tritium with the energy of 192 powerful laser beams. This process will cause the fusion fuel to ignite and burn, producing more energy than the energy in the laser pulse and creating a miniature star here on Earth (see How to Make a Star). With NIF, conditions are ideal for achieving fusion ignition, fusion burn and energy gain.

Ignition experiments at NIF will set the stage for one of the most exciting applications of inertial confinement fusion one could imagine—production of electricity in a fusion power plant.

To learn more about NIF's efforts to lay the groundwork for fusion energy—clean, safe, abundant energy for the future—visit the Laser Inertial Fusion Energy (LIFE) page on this Website or visit the LIFE Website.

Understanding the Universe

An artist's impression of Supernova SN 2006gy, the brightest supernova recorded to date.

An artist's impression of Supernova SN 2006gy, the brightest supernova recorded to date. Some of humankind's greatest intellectual challenges have to do with understanding how the universe began, how it works, and how it will end. A study by the National Research Council, Connecting Quarks to the Cosmos, produced a list of eleven questions that are crucial to advancing this understanding. Research at the National Ignition Facility could help answer five of these questions:

What is the nature of dark energy?

Scientists now believe that more than two-thirds of the universe consists of dark energy, a mysterious force that may be causing the universe to expand at an ever-faster rate. Attempts to deal with this question are in their infancy, but are currently more directed toward how dark energy acts than what it is. As a result, it will continue to be studied through one of the means by which it was discovered: using "Type Ia" supernovae—exploding stars—as the "standard candles" or measuring sticks with which cosmological distances are determined.But confidence in these measurements requires a detailed understanding of how these supernovae explode. Remarkably, computer simulations have shown that they are subject to the same hydrodynamic instabilities that affect inertial confinement fusion, the process at the heart of much of NIF's research (see How to Make a Star). NIF, then, will provide a unique way to study and understand these instabilities in the laboratory.

These same hydrodynamic instabilities also affect core-collapse supernovae, a different class of exploding stars that is also of great interest to astrophysicists. Understanding the explosion mechanism of these "Type II" supernovae has been a persistent problem in astrophysics for several decades. Current efforts appear to be focusing on instabilities as at least a factor in these huge explosions.

“The next two decades could see a significant transformation of our understanding of the origin and fate of the universe, of the laws that govern it, and even of our place within it.”

—Committee on the Physics of the Universe,

National Research Council

Did Einstein have the last word on gravity?

According to Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity, gravity results when any object with mass, such as our sun, warps the space and time around it. Determining if Einstein was right necessitates studying the objects in the universe that provide the most extreme gravitational effects—the supermassive objects in the center of galaxies called black holes, whose gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. Of course, black holes cannot be studied in the way that astronomers study most objects, by observing the light that they emit. The matter that swirls into a black hole, however, will be subject to an extraordinarily hostile environment. This means that this matter will be in a highly ionized state—the atoms will have been stripped of nearly all of their electrons. The radiation that results will be characteristic of those ions, so understanding them will provide a vast amount of information. Such ions are difficult to study in the laboratory, however, because the conditions that produce them are so extreme. NIF will be able to produce such ions in its intense x-ray environment and will provide data that will directly affect our ability to understand what is going on in the matter that surrounds a black hole.Ions in very high ionization states also affect other astrophysical environments, so the studies that will further our understanding of black holes will also provide insights into other astrophysical sites, such as the accreting neutron stars that produce x-ray bursts, and the regions around active galactic nuclei. The detailed knowledge of highly ionized ions will provide essential information about temperatures and densities in such extreme environments.

How do cosmic accelerators work and what are they accelerating?

The highest-energy cosmic rays in the universe have energies of around 1020 (100 quintillion) electron volts, many orders of magnitude greater than the highest energies that can be achieved in modern particle accelerators. How cosmic rays achieve those energies is not known, however; this is one of the questions posed by the NRC. NIF will produce extraordinary electric and magnetic fields in its most energetic shots, and thus should provide an environment in which particles acting in such extreme fields can be studied.What are the new states of matter at exceedingly high density and temperature?

NIF will provide the highest temperatures and densities that have ever been created in a laboratory environment, enabling experiments to produce states of matter unlike any previously achieved. These studies clearly will improve our understanding of materials in extreme conditions, and may also further our knowledge of stellar evolution, as well as of the inner structure of the largest planets such as Jupiter and Saturn.How were the elements from iron to uranium made?